Juan Garcia-Herreros (Snow Owl): Colors and Frequencies

9:30 AM, February morning, we are sitting in the cafe of the hotel «Intercontinental» in Moscow, ready to meet Juan García-Herreros, better known as Snow Owl, who truly is intercontinental person himself. Snow Owl is about to perform in the ongoing World of Hans Zimmer tour in Moscow. We had the chance to spend time with this versatile artist and to discuss the origins of his name Snow Owl, his indigenous roots, his US and African experiences, his views on music and what it was like to play with stars like Elton John or Hans Zimmer.

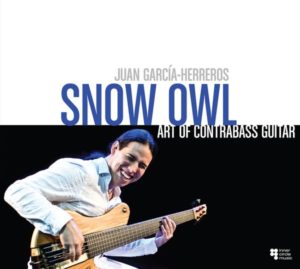

A week before this interview the person Juan Garcia-Herreros aka Snow Owl was mainly a mystery to us. Being just 42, he happened to be a Grammy nominee for «Best Latin Jazz Album» in 2014, a winner of three Gold Medals of the Global Music Awards and World’s Best Bass Player according to the reader’s poll of «Bass Guitar Magazine” and “Bass Player Magazine” . But his career started much earlier. Born in faraway Colombia he was forced, due to the drug war, to move to the USA at the age of nine where he discovered his passion for music. Later on he studied electric bass at the famous Berkeley College of music and started his professional career. Currently he lives in Austria, directs a sound design collective and composes music for Hollywood and the gaming industry.

A week before this interview the person Juan Garcia-Herreros aka Snow Owl was mainly a mystery to us. Being just 42, he happened to be a Grammy nominee for «Best Latin Jazz Album» in 2014, a winner of three Gold Medals of the Global Music Awards and World’s Best Bass Player according to the reader’s poll of «Bass Guitar Magazine” and “Bass Player Magazine” . But his career started much earlier. Born in faraway Colombia he was forced, due to the drug war, to move to the USA at the age of nine where he discovered his passion for music. Later on he studied electric bass at the famous Berkeley College of music and started his professional career. Currently he lives in Austria, directs a sound design collective and composes music for Hollywood and the gaming industry.

So far Snow Owl has published four albums: «Snow Owl Quartet» (2006), «Art of Contrabass Guitar» (2010), «Normas» (2013) and «The Blue Road» (2016). The latter being the first part of a philosophical trilogy about life and the world we live in. With the second part of this trilogy ”The Red Road», Snow Owl leaves the Jazz world and reveals the Rock side of his musical creativity. The album should have been released this summer but due to the crisis we have to wait until autumn to listen to it. (We’ve sent few additional questions about the new situation later via email, noted by «*»).

TOTEM SPIRITS

Okay, so let’s start with your nickname, Snow Owl. Is it a kind of totem animal?

Okay, so let’s start with your nickname, Snow Owl. Is it a kind of totem animal?

Absolutely. I hope I pronounce it right: Is it Shnezhnaya Sova in Russian? I tried to practice that. (laughs) Yes, I come from the Arhuaco and Wayuu tribe in Colombia. Our totem spirits are very important to us. When I was born, the chief of our tribe said that a white owl brought me from the spirit world into the physical world. That’s the reason for my name.

So you have indigenous roots, this must be a lifelong inspiration.

Yes, it is. The teachings and wisdom from our nation still apply to this modern, fast and technical world. The things we have learned over thousands of years still help us to be good human beings and to be connected with nature instead of machines.

Currently you are working on a philosophical musical trilogy, the second part will be released soon. The first album, “The Blue Road” reveals a person’s spiritual path?

Yes, that is correct.

And the next one, as we know, will be about the warrior’s path, and the third one will be some kind of combination…

And the next one, as we know, will be about the warrior’s path, and the third one will be some kind of combination…

Yes, the yellow road is the balance between the blue and the red road.

So these paths are part of your indigenous philosophy?

Yes. We believe that every soul choses a color — a road in its life. The blue road, the red road or the yellow road. For example there are people who bring messages from the spirit world, or others who came here to be warriors. Then there are people who live both forms in a balanced way. I tried to apply this concept into everything I do. How can a warrior communicate with the spirit? How can the spirit communicate with the warrior?

What I also love about the three colors, the yellow, blue and red: these are the colors of the Colombian flag. But that’s a coincidence.

There is also a fourth road, which is enlightenment and it is just white. Then you’ve entered the light.

How you choose the musical colors to represent those physical colors?

Music is frequency and colors are frequencies too. It is very easy for me to connect a sound to a color. For example there are dark tones and high tones which are brighter, the same as there are brighter colors and darker colors. Certain melodies can be associated immediately with water, fire or with air. So actually I just give sound to what I see.

NOTHING IS IMPOSSIBLE

A simple question, why you choose a bass guitar at first?

A simple question, why you choose a bass guitar at first?

My brother was learning drums. And he said: I need a bass player. And I didn’t want to play… And he was like: Nah, come on… And I started to play right away with him, we started with songs like Led Zeppelin, Metallica, Megadeth, with all the rock stuff. These are the first things that I was playing on the bass.

How old were you then?

14.

Who are the musicians that influenced you?

So many of them! Cliff Burton from Metallica, he’s my big idol, John Paul Jones from Led Zeppelin, great Jaco Pastorius, absolutely great. Dave Ellefson from Megadeth, Tony Levin from King Crimson. All of these bass players have really inspired me.

Did you listen to their music or watch their videos?

When I was living in Florida, there weren’t any music videos at the time. There were some radio stations that would play eclectic music at two in the morning and I would stay up and record it on cassettes. Then I would learn what I heard on the radio.

But was it difficult to learn that way?

But was it difficult to learn that way?

Because I didn’t have a teacher in the beginning, nothing was impossible. If I heard it on a recording, it was possible. If I heard a great bass player do something really fast, I knew that it’s possible. So I didn’t have to think of technique, I would just try to copy it. In the end you have to be fearless to have a good technique!

As we know from your biography, first you were self-taught musician, then you went through Berkeley School.

Right.

So what is the balance between finding your own path and learning from the others, from the established system of education?

I think that when you teach yourself it has advantages and disadvantages. Because you’re going to do things without anybody telling you that’s wrong. So you’re free. But you’re also limited. When I first went to Berkeley, I won the scholarship to go there. I only went there for one year. My teacher saw my dedication, my discipline, and he told me: look at these books, look at these techniques, but, he said, you don’t need the school, go make a career. That’s what he said: «Just go». And it was a hard decision, because you always hear: you should have a master’s degree, or you should have this or that, but I really had faith that my teacher was supporting me, and he told me go to New York and start my career.

What was the name of your teacher?

What was the name of your teacher?

Bruce Gertz. And we’re still in contact, he’s great friend. And the Academy has good sides and negative sides. Because it’s very difficult to find one formula that will make every artist reach their potential. So it’s like a general platform, like, you should learn this, you should that… But for a lot of people, it doesn’t help them to become the artists that they are. Because these subjects are not illuminating their possibilities. For some artists that might open up their mind to great things, Berkeley is a great school. It’s absolutely amazing. But there’s other artists, their vision is so clear that the school can be very dangerous for them.

You have played in America with a lot of bands from the metal and rock area. Any names we can recognize?

At that time they were not very famous, underground bands in New York City. A lot of bands in CBGG, you know the famous club, I miss it so much. Tritone was one of them, that was a really good, Shadow Call was another one. Maybe in New York they had a little bit of a following but it was very underground. I had to work pretty fast into like studio recordings and Broadway shows and to survive, because you have to pay the rent. So I had to do all those things, you know, on the side as well.

Speaking of Broadway shows, can you name few that were the most important for you?

I played «Chicago». I enjoyed that very much, that was wonderful. I also played «Cats» and «Jesus Christ Superstar». All those shows are very nice. I also was playing a lot of salsa music in New York City from the Latin community. So I was playing with Marc Anthony, and all those big salsa names. But in my heart, it was always between heavy metal and jazz. So that’s what I was doing when the work was over, I was going to the late clubs to play jazz, or to play rock. It’s something I’ve always loved.

CITIZEN OF THE WORLD

So you grew up in America, can you please tell why you’ve moved there?

So you grew up in America, can you please tell why you’ve moved there?

I had to move to America. There were terrible wars going on in Colombia, the guerrilla war, the drug war and it was very difficult for my family and my uncle. My uncle, padre García-Herreros, brought Pablo Escobar to jail and that was a big problem for my family. It was dangerous for us, therefore we had to leave. In the beginning it was not easy for me to relate to Americans. They have a certain way of seeing life. They have a lot of confidence because they hear every day that they are the greatest. I never agreed with that, because the world is very big (laughs). There’s so much out there. Looking at the world through one country’s eyes was not enough for me. I wanted to know the world from every country’s perspective and be a true human being with human values that are broader than just a zip code.

What have you learned from this country?

I’m very grateful for that in America I have learned the importance of confidence and business in an artist’s life. But when it came to spirit and human qualities, I had to leave the United States to find out more.

Why have you moved to Austria?

There was an opening in the University of Arts for a professor of electric bass. And they asked me in New York to come to be the professor. And I love the idea of coming to Europe learning German, and also studying classical composition. So I was teaching and also studying at the same time. So it was thanks to the University that I came to Austria.

You’re only teaching, you don’t do anything like musicology researches?

You’re only teaching, you don’t do anything like musicology researches?

I do. I’m fascinated with music phenomenology right now. There’s always something that I’m researching, and right now I’m in the Jam Lab private University and focusing on the masters. So every master’s candidate that I supervise has a research project. So that is what I’m interested in.

I’ve heard that you lived in Africa for some time, learning local music? When and where it was?

That was about seven years ago, in Burkina Faso. With the Griot tribe, the Diabaté tribe.

They are famous for their music…

Yes they are. You know, it was very beautiful, when their chief, the Grand Griot from Diabaté saw me for the first time he said to me: «Sajuma». And I was like, Sajuma, what is that? And he said: «White Owl». That was incredible.

How did you find a common language with the African musicians?

How did you find a common language with the African musicians?

Through rhythm. And through the balafon. Do you know this instrument?

It’s some kind of xylophone, right?

Correct, it’s the West African xylophone and the balafon notes actually are a language. Each melody means something. So in the morning, when Mamadou Diabaté would wake up, he would play a melody and his neighbour would bring him milk or they would say hello between the villagers with the balafon. It was easy for me to learn the notes and some of the phrases so that we could start communicating.

It’s like a telegraph.

Yeah, like a Morse code. A musical Morse code.

Have you learned the local language? Is it French?

Bambara. It was difficult, but learned it as much as I could.

You have a rich musical legacy of your country, and yet you combine it with other cultural backgrounds like African or Bulgarian. Why do you feel this need?

You have a rich musical legacy of your country, and yet you combine it with other cultural backgrounds like African or Bulgarian. Why do you feel this need?

I wanted every album to be a union of the tribes of every nation. For example, in Colombia we have a lot of Afro Caribbean rhythms which I love. Okay, the Caribbean side I always understood, it’s Colombian, but I never understood the African side. So I went to Africa and lived with an African tribe for two years. I learned their rhythms and their language because I wanted to understand the tribal history. I wanted to understand how all of this was connected to Colombia. In the end, the final and true question for me always is: What is the sound of my time? And for that I need to understand our musical history. My responsibility as a musician is to document the sound of now. Every conflict, every happiness, every triumph, everything should be documented by me as a musician. Therefore I want to include as many nations as possible, because I believe we are one at the end of the day.

36 INCHES OF SOUND

You’re coming to Moscow; have you ever been here before?

Yes, we presented «The Art of Contrabass Guitar» in Moscow, at the «Mir» theater, «The World» theater, am I right?

Yes!

Yes!

My band from «The Art of Contrabass Guitar» was here and we presented the CD. It’s on my Instagram (laughs). There was a huge poster of me on the street, and it was very beautiful.

How it went?

Very well. I really hope to bring «The Red Road» to Moscow as well.

Your second album is called «The Art of Contrabass Guitar». So what is the contrabass guitar? Is it just a six string bass or something special?

Anthony Jackson discovered the contrabass guitar. It has the six stings, but it’s not a six string bass, because it’s a fixed scale, the size has to be 36 inches. And the contrabass guitar has 28 frets. More standard bases are maybe 21-22 frets. This is designed like, you know, you have a clarinet and you have a bass clarinet; you have a guitar and a contrabass guitar. That’s what it is.

So it has a longer neck?

A very long neck, like standard string length for the B string is the length of an upright piano. More frets, bigger neck for the sound and it’s a very specific construction, so contrabass guitar is very specific.

Is the way of playing on it somehow different?

Is the way of playing on it somehow different?

Yes, because there are so many strings, on the four string bass you don’t have the problem of muting. Because the strings vibrate very easily, they start to ring. So you always have to put your hands, these two fingers, you have to put them down to hold the strings so they don’t ring. It’s very difficult to play, because you have to play literally like this all the time. So yeah, the technique is very specific.

But you also use slap…

Yes. Slap. Beats. Electronics. Distortions. Lots of stuff.

But despite having such interesting array of techniques and instruments, you don’t overuse the showing in the technique in your music.

No, because you need to play what the music asks for. I could solo all the time. That’s boring. That’s like somebody who doesn’t stop talking. And we need to focus on what is the music asking for. And that’s where you have to be a very sensitive mature musician.

Do you like to listen to the music that showing the bass right out? I mean something like Stu Hamm or Marcus Miller…

Well, we’re all friends. Victor Wooten, Marcus, Stu Hamm, we play a lot of bass guitar shows together. We know each other from backrooms, backstage and everything. I listened to some of their music. But, you know, for me there’s not a lot of difference between a Marcus Miller bass solo and the Beethoven Symphony music, because there’s the whole purpose of bass is to be a supporting counterpoint melody. Sometimes can be the main melody, sometimes can be a counterpoint. So, if it’s a great baseline, if it works in the music, that’s what I’m loving, that’s what I’m looking for.

There were some tunes on “The Blue Road” (for example, a track named “Bach to the Future” – ed.) that show an interesting combination of almost Baroque music, something that sounds like Vivaldi, like a little quote from «Four Seasons”.

There were some tunes on “The Blue Road” (for example, a track named “Bach to the Future” – ed.) that show an interesting combination of almost Baroque music, something that sounds like Vivaldi, like a little quote from «Four Seasons”.

Yes (Smiles.) Maybe subconsciously… I have a great affinity for classical music and I’ve studied it my whole life. I’m still studying it! I’ve been very lucky to be one of the few electric bass players that work with orchestras. I’ve worked with the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic, the Hans Zimmer Orchestra as well, Hollywood films, everything. It’s a very new way for the electric bass, because usually orchestras have an acoustic bass. So you need a very good knowledge of classical music. You have to know the phrasing, the movements, the dynamics. Otherwise, the other musicians will be shocked by you.

BETTER THAN THE FILM

It’s time to ask about Hans Zimmer and his orchestra. What have you learned from playing with him?

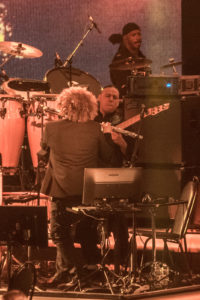

A lot! First thing that I have to say about Hans Zimmer is that he selects the musicians very smartly. He knows all of our abilities and he trusts us. He lets us be the artists. And he never tells us play this note and that note. He gives us a platform, and we improvise on it. We’re nine soloists with the orchestra and we improvise with the orchestra every night. It’s really fascinating.

Cool! We thought that you’re playing written, sheet music.

Cool! We thought that you’re playing written, sheet music.

There was a sketch in the beginning, like, maybe this, maybe that… But what we do is we’ve stretched it, we have expanded the music. And our goal with the World of Hans Zimmer is… Everybody loves those movies, right? We want to be better than the movies. We want that the music brings the people to the movies again, and it’s a full circle.

But what about someone who haven’t seen the movies? Will he be impressed same way?

Yes… Actually, I feel sorry for the person that sees the show first, and then the movie. Because in the movie the music is sometimes very low in the background, because of action scenes, or whatever. So they might fall in love with the music more, which is good. (Laughs.)

And you say that Hans Zimmer invited musicians very carefully and wisely. Has he ever told you why he chose you?

First, the contrabass guitar, right is an instrument that goes very low, extremely low. And he knows how to use the lowest frequencies possible. He’s a master of that, because of all the things that he used to program and work with. So one of the reasons is he loves my sound in the low registers and he loves my soloing capabilities. I can be very melodic, but I can also be very low and rhythmical. And he has many times told me that he has never seen anybody play the bass like me in the world.

Had he ever told you something like you can do that, or you need to do this?

Had he ever told you something like you can do that, or you need to do this?

No, no! Actually it’s funny, one time he said to us: «Play the wrong notes with conviction!» (Laughs.) «Play as many wrong notes as you want!» He’s very open. Because he knows we’re musical. He trusts us. So we trust him.

You’ve got some your own projects in film area, right?

Yes. I have a sound design company called «Totem Warriors». It’s in Vienna and focusing on soundtracks, films, TV or video games, and that’s one of the next areas which I feel it’s very important to be involved in right now. Because the only way that children are receiving orchestral music right now is through movies or video games. So there can be another way of getting them to love orchestral music. Because at the end of the day, my only wish is that to create more musicians instead of lose musicians to the machines. So I’m always trying to find ways that I can communicate with bigger audience. So that’s the reason for the «Totem Warriors».

Recently you became an Air-Edel artist, what does this mean to you?*

Recently you became an Air-Edel artist, what does this mean to you?*

It is a great honour and privilege to be associated with such an important company that has literally invented film music productions, with the legacy of George Martin and Hans Zimmer.

How the situation with coronavirus affected your life?*

It affected my life in a profound way, for now we don’t know, when it will be possible to play concert tours again. But I always find ways to see the positive and adapted to the situation. I enjoy having more time to compose music for movie productions and video games.

HEAVY WORLD MUSIC

Let’s speak again about your own music. Will the upcoming album, «The Red Road» be harder, more metal than the previous?

Yes, absolutely. It’s gonna be hard rock, heavy metal… I actually call it «heavy world», world music with heavy metal riffs. There are some beautiful surprises in there. I collaborated with a great Russian cimbalom player on The Red Road, her name is Anna Baulina, and there is one particular song that means a lot to me. In this song 13 different tribes sing together over a big percussion section. The album has a very strong message about why we are suffering so much as human beings right now and how we need to change that consciously on a global scale. Life doesn’t have to be a struggle, or a fight. There is another way. That’s what we’re showing. We’re fighting, we’re being warriors, we’re fighting for a better world.

But is it possible to change our minds with the music?

But is it possible to change our minds with the music?

Absolutely. It starts with yourself. If you want to see any change in the world, you have to change yourself first. If you set an example, other people will be inspired by you, and then they’ll copy and follow. So of course it’s possible. If it wasn’t possible, we wouldn’t be alive today, all of us as a human race. Look at all the changes that have happened in the church оver the years. How many changes have happened in politics. How many changes have happened socially and politically and between religions and sexuality and… There are so many changes that are happening all the time. So it is possible… as long as we’re taking care of each other. I think that’s the thing we were forgetting. We’re looking at Instagram, we’re looking at Facebook, with me, me, me, it’s very narcissistic. We want to show that our lives are great with these fake photos. But we’re forgetting that the rule number one is we have to take care of each other. And if we put that inside, that’s where the change will come.

In some of your songs we hear some strong progressive rock influences. «The Horde» (the first single from “The Red Road” – ed.) sounds a little bit like the French band Magma…

In some of your songs we hear some strong progressive rock influences. «The Horde» (the first single from “The Red Road” – ed.) sounds a little bit like the French band Magma…

The rhythms are from Balkan and Turkish areas, which, for me, are the red colored rhythms. It can be seen as progressive because there are so many different odd meters and solos, it’s just a marriage of great cultures into one song. I encourage the readers to also take the time to read the lyrics because they convey a powerful message about the world we are living in.

I have to say that, until now, every album that I did was instrumental. But now with «The Red Road», I realized that what I’m trying to say is very limited if it’s just instrumental music. I need lyrics so people get a deeper meaning of what I’m trying to say, so almost every song on «The Red Road» has lyrics now. There’s only one instrumental track in the whole album. And that’s a new thing for me as well.

Who are the singers on «The Horde»?

The female voice is Ganya, the opera singer, she’s amazing. And I always wanted to put her inside of my music. And Matthias who is the hard rock singer from Austria, he’s from the from the heavy metal scene from Austria.

What is the band he plays with?

Dhark. He was playing with the bands Dhark and Prometheus. He was very prominent with those bands.

How do you choose the musicians to work with?

I’m always looking for musicians that people don’t know to surprise them. I always want to find combinations of musicians that nobody has ever heard of. And then say — look at this musician, look what we can do together. So I like to surprise the audience with hopeful musicians they never knew. Like on the «Red Road» I even put in a Russian cimbalom. By a great Russian cimbalonist, her name is Anna Baulina.

There is a song on a «The Blue Road» album, «She Became A Thousand Birds”, very deep and touching track… (There is a tribute song to a girl that died in a catastrophic earthquake in Colombia in 1985, — ed.)

There is a song on a «The Blue Road» album, «She Became A Thousand Birds”, very deep and touching track… (There is a tribute song to a girl that died in a catastrophic earthquake in Colombia in 1985, — ed.)

That song was a strong political statement to criticise the Colombian government about disaster prevention and response. The region still needs help after 30 years! I wanted to say to the Colombian government: don’t forget what happened, don’t forget the 23,000 victims, don’t forget the 13 year old Omayra Sanchez! The song was received well, even by the Cannes Film Festival, and it had an impact in Colombia. The politicians changed the policy because of the song. This is how powerful music can be.

Please tell about a female singer on the track? It’s a beautiful voice!

Her name is Such, she’s from United States. She’s half Haitian, half American, African American. She’s a fantastic soul singer. And she is the perfect voice for that tribute song for Omayra.

By the way, are you singing yourself?

Yes, sometimes. In the album, «The Red Road», I’ll be singing too.

When «The Red Road» will be out?*

I wanted to release it in July but now everything changed. Our first tour with the album in South America had to be cancelled and therefore I decided to postpone the release to Autumn.

When do you plan to make the third part?

Usually it is a two to three year cycle that I publish a new album. For these albums I might need some more time, because I have to change profoundly inside of myself. I have to “switch roads”! The change from the spiritual to the warrior’s road took me some time. I was more of a blue person before (laughs). I can’t possibly predict how long it will take me to change from the red to the yellow road.

IN LOVE WITH BALALAIKA

One step in your career was working with Elton John. What kind of work was it?

One step in your career was working with Elton John. What kind of work was it?

Touring. There was the big Australia tour with orchestra, I was on that.

Was there any personal interaction?

Yes. Oh my God, he’s a great musician! And I love him so much because he really sings! (Smiles) You know, there are so many singers who perform with playback, and he sings everything. He plays everything. I learned from him the importance of creating a show, an experience. His fans loved him because they never knew what costume, what glasses he would wear he always had these elaborate shows that really made it special. So I thought, wow, you can’t just walk on stage and not have a good outfit, a good show, because people will be bored. You have to give them something visual as well. That’s something that I’ve learned from him.

You won the reader’s poll as the world’s Best Bass Player in «Bass Player Magazine” and “Bass Guitar Magazine”. How do you feel about that?

You won the reader’s poll as the world’s Best Bass Player in «Bass Player Magazine” and “Bass Guitar Magazine”. How do you feel about that?

(Laughs) Well, it’s impossible to say who is the best, but I think it’s a great honour, because a Colombian never won that recognition. It was a world vote, the magazines nominated 20 bassists, and I’m very happy for my country. Maybe the world will look at Colombian bassists in a different way now. I’m grateful for the recognition but at the same time I wasn’t looking for it. (Smiles)

I just got a phone call from the magazine, and they said: «We nominated you». I said, thank you, that’s very nice, pretty wonderful. And then, you know, a few months later, the editor from this magazine called me in Norway, and he said: «Guess who won the votes?» And I said: «Oh, for sure Stanley Clarke or Stu Hamm»… And he said: «No, you won!» And I said: «That’s very funny. Who won?» And he said multiple times: «You won!» And I said: «Oh my God…» I was in shock.

So it’s a great honour, but it makes me work harder. I don’t want to reach this point in my life and then just stop. It inspires me to work harder.

Do you know any Russian bass players?

Well, I love this balalaika thing. (Stretches hands wide…)

Bass balalaika?

Bass balalaika?

Yes, I love that instrument. It is so beautiful, so big, I love it. I’ve been a professor for many Russian bass players in Austria. Young ones, very talented…

Is there something that you might advise to Russian musicians?

The thing that I always want to say to any bass player is: play what the music is asking for. Be true to yourself. And don’t be afraid to take risks. Because you only have this musical life. And you don’t want to sit back and think: should I have played this, should I have done that? Music has no limits. Music is a gift that we can share with each other. So we shouldn’t pressure ourselves about right or wrong. We should only focus on expressing the human spirit. So that’s what I would say to the Russian bass players.

Elena Savitskaya

Vladimir Impaler

Thanks to Mona Müller for organising this interview.

Photos — Vladimir Impaler.

Russian version of the interview: http://inrock.ru/interviews/snow_owl_ru_2020